Achieving and sustaining zero CLABSI – yes, we can!

Central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) remain a significant patient safety issue in intensive care environments, where central venous catheters (CVCs) are frequently essential for patient care. CLABSI is associated with avoidable morbidity, mortality risk, longer length of stay, and substantial excess cost. Against this backdrop, longitudinal improvement programmes that achieve sustained reductions, particularly sustained “zero”, offer useful insights into implementation, reliability, and system performance.

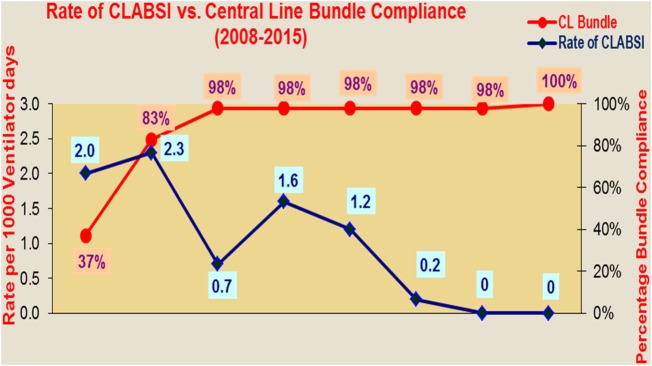

For Journal Club this week, Dr Yaseen Muhammad will be reviewing an article describing a quality improvement programme at King Abdulaziz Medical City Jeddah (KAMC‑J) in Saudi Arabia reporting a reduction in adult ICU CLABSI from an average 2.0 per 1,000 line-days in 2008 (with 37% bundle compliance) to zero CLABSI in 2014, sustained through 2015, alongside a remarkable 100% reported compliance with the IHI Central Line Bundle.

This post focuses on what the programme suggests scientifically about bundle implementation, surveillance, and high‑reliability infection prevention—while also being clear about the academic limitations inherent in the study design.

Baseline: a high-risk setting with sub-optimal process reliability

The baseline condition, with moderate CLABSI incidence with low compliance to an evidence-based prevention bundle, is a familiar pattern in device-associated infection prevention. At KAMC‑J, baseline bundle compliance was 37%, suggesting that a large proportion of insertions and/or ongoing care processes deviated from best practice. Importantly, the bundle was measured using an “all‑or‑nothing” approach: if any element was missing, the episode was scored as non‑compliant. This doesn’t capture “partial compliance” with the prevention bundle, but makes sense because there’s a bundle of measures recommended for a reason!

Intervention: a multi-component implementation strategy

A multidisciplinary team was established and adopted the IHI Central Line Bundle elements:

- Hand hygiene

- Maximal barrier precautions

- Chlorhexidine skin antisepsis

- Optimal catheter site selection (subclavian preferred)

- Daily review of line necessity

The programme incorporated education, “train‑the‑trainer” competency building, monitoring of compliance, regular feedback to clinical teams, and iterative quality improvement cycles (FOCUS‑PDSA). Supply reliability (e.g., ensuring alcohol-chlorhexidine availability) was addressed (a common frustration of ward staff that isn’t often addressed in an academic setting!).

Outcomes & interpretation: a dose–response relationship between compliance and CLABSI

The reported trajectory is consistent with a process-outcome relationship: as compliance increased towards 98–100%, CLABSI rates declined, eventually reaching zero and remaining there for two years (see the image). Sustained zero, particularly in an ICU environment with ongoing central line utilisation, is a real success and suggests that system change was achieved – hearts and minds were won!

Image: Compliance to prevention bundle vs. CLABSI events.

From an implementation science perspective, several mechanisms plausibly contributed:

- Standardisation of insertion and maintenance behaviours

- Measurement and feedback loops that increase accountability and situational awareness

- Multidisciplinary ownership, reducing gaps between professions

- Persistence in addressing clinical preference barriers (e.g., reluctance to use the sub-clavian site)

- Operational support (equipment and consumable supply), enabling staff to “do the right thing” consistently

Limitations and methodological considerations

As ever, there are several academic limitations to consider:

- Study design: this was a single centre, non-randomised, observational, quality improvement project without a contemporaneous control ICU. Therefore, we can’t be sure that the improvements were related directly to the intervention. And this limits the generalisability of the study.

- Potential confounding: multi-year programmes typically involve multiple simultaneous changes beyond the specified intervention (e.g., changes in staff mix, training intensity, insertion technique, catheter technology, antimicrobial stewardship, maintenance practices).

- Compliance measurement: measurement of bundle compliance was a key component of this study. This measurement is prone to observation bias (aka the Hawthorne effect, when behaviour changes when people are monitored), documentation bias, observer bias (where subjective elements of compliance measurement vary by the observer),

- Rare-event interpretation: “zero” is meaningful but statistically complex. Confidence intervals around a rate of zero depend on the number of line-days observed. Sustained zero is impressive, but it may still be compatible with a very low non-zero underlying rate.

Summary

The KAMC-J programme provides an impressive longitudinal example of how effective implementation of an evidence-based central line bundle, supported by multidisciplinary leadership, surveillance, and feedback, can be associated with dramatic CLABSI reduction and sustained “zero” outcomes.

Academically, limitations typical of QI studies (non-randomised design, potential confounding, and compliance measurement biases) mean the results should be interpreted as compelling practice-based evidence rather than definitive proof. Nonetheless, the findings really do suggest that we can get to zero CLABSI and sustain it!

Subscribe

Subscribe to our email list if you’d like us to let you know about future Journal Clubs and for other updates from IPC Partners.

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. Learn more