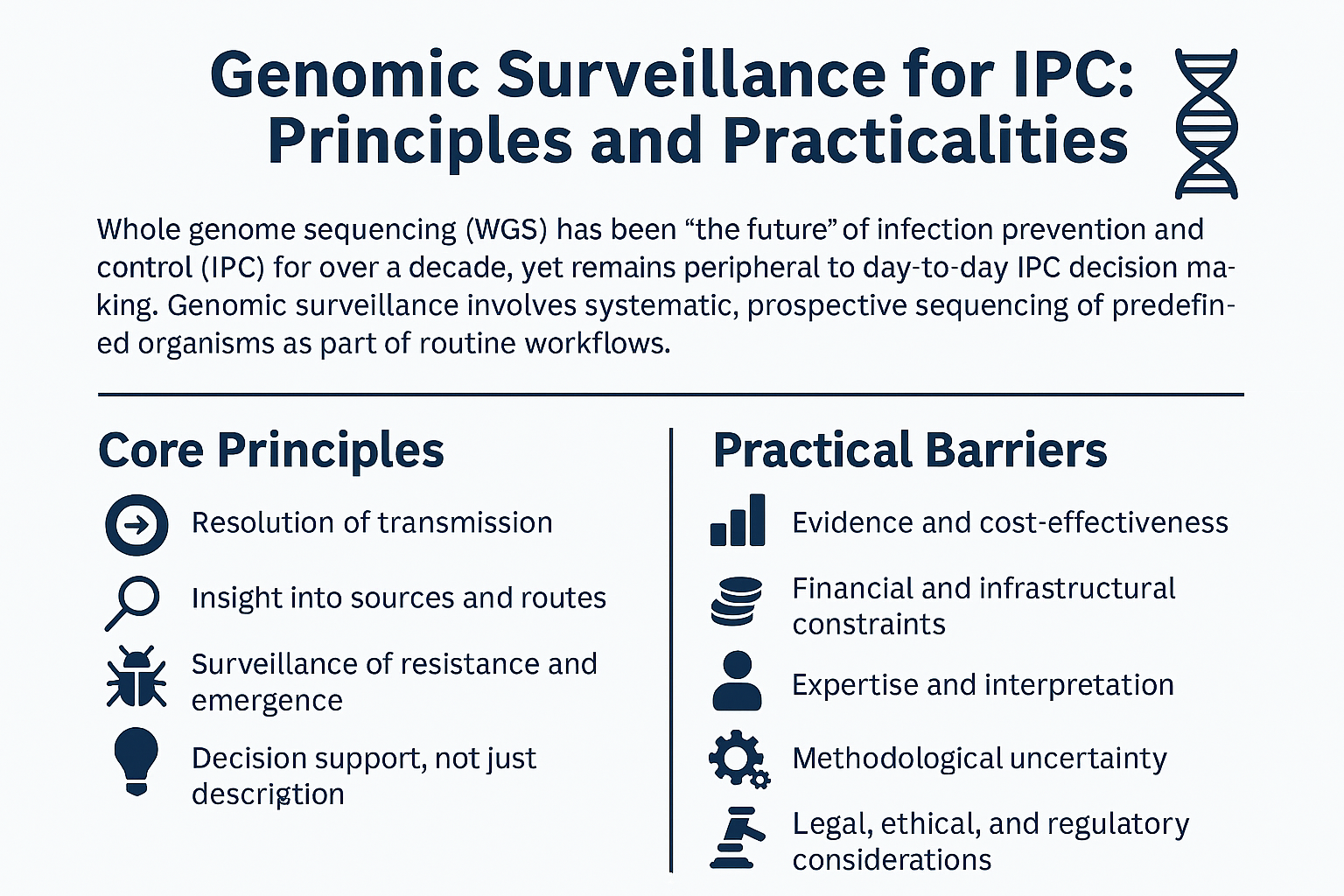

Genomic surveillance for IPC: principles and practicalities

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) has been “the future” of infection prevention and control (IPC) for an uncomfortably long time. For well over a decade, we have understood, at least in principle, that genomic data can transform how we detect transmission, investigate outbreaks, and understand the epidemiology of healthcare‑associated pathogens. And yet, in most healthcare settings, WGS remains either non-existent or peripheral to day‑to‑day IPC decision making.

In this blog, I reflect on the core principles that underpin genomic surveillance for IPC, and what does it will take to move from reactive, research‑led sequencing to prospective, operational use that genuinely informs IPC action. Already looking forward to Dr Alexander Sundermann's Insight Webinar on this topic (you can register for that here).

What do we mean by genomic surveillance for IPC?

Genomic surveillance is often conflated with outbreak sequencing, but they are not the same thing. Reactive sequencing - sending a handful of isolates to a reference laboratory once an outbreak is suspected - can be valuable, but it is inherently limited. It answers a narrow question, late in the day.

Genomic surveillance, by contrast, is systematic and prospective. It involves sequencing predefined organisms (for example, all CPE, all C. auris, or all invasive Staphylococcus aureus) as part of routine workflows, so that when a new isolate appears it can be interpreted in the context of local, national, or even international genomic data close to real-time.

Core principles: what WGS offers IPC

There are four principles that consistently emerge when WGS is applied at scale to healthcare pathogens.

1. Resolution of transmission

The most compelling contribution of WGS to IPC is its ability to rule transmission in or out with far greater confidence than traditional typing methods. Time and again, large studies show that many presumed outbreaks are not outbreaks at all, while at the same time revealing “cryptic” transmission that was missed by conventional surveillance.

This has operational impact. If transmission is ruled out by WGS, precious IPC resource does not need to be diverted into contact tracing, ward closures, or environmental sampling. Conversely, identifying previously unrecognised transmission allows targeted intervention where it is most likely to have impact - and before outbreaks get out of control.

2. Insight into sources and routes

Genomics has repeatedly challenged our assumptions about where pathogens come from and how they spread. High‑profile examples include globally distributed point sources, such as contaminated heater–cooler units in Mycobacterium chimaera, or reusable equipment linked to C. auris. At the same time, WGS has shown that some organisms spread far less via direct cross‑transmission than we once believed.

For IPC teams, this shifts the focus from reflexive assumptions towards evidence‑based interventions.

3. Surveillance of resistance and emergence

At scale, genomic data allow us to track antimicrobial resistance mechanisms, clonal expansion, and plasmid‑mediated spread across institutions and regions. This is particularly important for organisms such as CPE, where understanding whether increases are driven by transmission, importation, or horizontal gene transfer has direct implications for control strategies.

4. Decision support, not just description

Finally, genomic data are only useful if they inform decisions. The principle here is not academic completeness, but actionable interpretation. WGS should answer IPC‑relevant questions: Is this transmission? Is this ongoing? Is this unusual? And what should we do differently as a result?

Practical barriers: why is this still hard?

If the principles are so compelling, why has prospective genomic surveillance been so slow to embed in routine IPC? The barriers are well described, and broadly fall into six overlapping domains.

1. Evidence and cost‑effectiveness

Although the body of evidence is growing, many healthcare systems still struggle with the absence of definitive, context‑specific data showing reductions in infection or clear cost savings. WGS is not free at the point of use, and decision‑makers understandably ask how sequencing costs balance against prevented infections, avoided outbreaks, or reduced bed closures.

The challenge is that many benefits of WGS are indirect, and accrue over time rather than as headline‑grabbing immediate wins and cost savings.

2. Financial and infrastructural constraints

Establishing local sequencing capacity requires capital investment, laboratory space, and ongoing consumable and staffing costs. Not every hospital has a molecular laboratory capable of supporting WGS, and even fewer have on‑site bioinformatics expertise.

Outsourcing sequencing can mitigate some of these challenges, but introduces others, particularly around turnaround time and integration with local IPC workflows.

3. Expertise and interpretation

Generating sequence data is no longer the hardest part. Interpreting it in a way that is robust, reproducible, and meaningful for IPC remains a major challenge. There is still no universal agreement on analytical pipelines, thresholds for relatedness, or how to interpret genomic distance in different epidemiological contexts.

This is compounded by workforce issues. Bioinformaticians and genomic epidemiologists are in short supply, and IPC teams cannot reasonably be expected to bridge that gap alone.

4. Methodological uncertainty

Even at a technical level, there is ongoing debate. Short‑read versus long‑read platforms, the role of hybrid assemblies, organism‑specific approaches, and how best to incorporate non‑bacterial pathogens all remain active areas of discussion.

Perhaps more fundamentally, there is still disagreement about when and how WGS should be used: reactively, prospectively, or as a hybrid of both.

5. Timeliness

For IPC, late information is often no use. f genomic results arrive weeks after decisions have been made, their operational value is limited. Achieving clinically relevant turnaround times (i.e. days rather than weeks) is essential if WGS is to inform real‑world IPC action.

6. Legal, ethical, and regulatory considerations

Genomic data raise legitimate concerns about data security, patient confidentiality, and governance. There are also more subtle issues: how should healthcare organisations respond to the increased resolution of transmission events? Will we identify so many small clusters that IPC teams become overwhelmed, or distracted from the events that matter most?

Regulatory frameworks and quality standards are evolving, but inevitably lag behind technological capability.

Moving from theory to practice

Despite these challenges, there is real momentum. The most promising developments share a common theme: integration.

Successful genomic surveillance programmes do not treat WGS as an add‑on, but as part of an end‑to‑end system linking laboratory workflows, bioinformatics, epidemiology, and IPC decision making. This often means starting small (focusing on a limited number of high‑impact organisms) and building iteratively as confidence and capability grow.

Prospective sequencing, in particular, changes the dynamic. When baseline data already exist, each new isolate becomes immediately interpretable in building a bigger picture, rather than an isolated puzzle piece. This is where genomics begins to feel less like research and more like routine surveillance.

Looking ahead

I remain convinced that genomic surveillance will become a standard component of IPC over the next few years. Not because it is fashionable or technologically impressive, but because it addresses questions that IPC teams grapple with every day: Are we seeing transmission? Does this cluster matter? And where should we focus our efforts and resources?

To get there, we need to be honest about both the power and the limitations of WGS. Genomics will not replace good IPC practice, but it can make it smarter, more targeted, and more proportionate. The challenge now is not to prove that WGS works in principle, but to make it work in practice - reliably, affordably, and at the pace that IPC demands.

Subscribe

Subscribe to our email list if you’d like us to let you know about future Journal Clubs and for other updates from IPC Partners.

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. Learn more